The Ancient City of Luna

Se tu riguardi Luni e Urbisaglia

come sono ite, e come se ne vanno

di retro ad esse Chiusi e Sinigaglia,

udir come le schiatte si disfanno

non ti parrà nova cosa né forte,

poscia che le cittadi termine hanno.

Dante Alighieri, Divina Commedia,

Paradiso, XVI, 73-79

History and Archaology

At the beginning of the 2nd century BCE, the Romans began frequenting the area where the city of Luna would later be founded, using its port as a strategic base for the conquest of Spain.

After repeated clashes with the Liguri Apuani and their eventual deportation to Samnium, in 177 BCE, two thousand Roman citizens took part in the founding of the colony of Luna. The initiative was promoted by the triumvirs Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, Publius Aelius Tubero, and Gnaeus Sicinius. Each settler was granted 13 hectares of land in an area roughly between the Magra River and what is now the municipality of Pietrasanta.

Despite the permanent Roman settlement, hostilities with the Liguri Apuani continued. It was only in 155 BCE that they were definitively defeated by Consul Marcus Claudius Marcellus. To commemorate his triumph, a monument bearing a statue of the victorious general was erected in the central area of the colony.

-

Portrait identified as Marcus Aemilius Lepidus

Portrait identified as Marcus Aemilius Lepidus -

Honorary inscription of Consul C. Marcellus who achieved the definitive triumph over the Ligurians

Honorary inscription of Consul C. Marcellus who achieved the definitive triumph over the Ligurians

The City in the Republican Age

The defensive walls and the urban layout — characterized by a grid of streets intersecting at right angles to form rectangular blocks (decumani, running east–west, and cardines, running north–south) — can be traced back to the earliest phases of the colony.

During this period, both public and private buildings were constructed, many of which were later renovated or completely replaced.

Particularly significant were the places of worship, such as the Temple of the goddess Luna, notable for its terracotta pediments inspired by Rhodian and Pergamene sculpture, and the Capitolium, which was refurbished in the late 2nd or early 1st century BCE, adopting stylistic elements from Hellenistic architecture.

The Imperial Phase

After 42 BCE, Octavian (the future Augustus) granted new land allotments to his veterans in Luna, as evidenced by a reorganization of the agrarian divisions that replaced the previous layout.

In the early decades of the 1st century CE, under the rule of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, the great monuments of the city center were constructed, replacing many of the older buildings.

Monumental complexes were built along the sides of these new structures, connected by open walkways that led to two additional squares and eventually to the Cardo Maximus.

On the eastern side of the Forum, an entire privately-owned city block was demolished to make way for an impressive temple framed by a portico, with access from the Decumanus Maximus — this is the so-called Temple of Diana.

Adjacent to the Capitolium, the eastern wing of the triporticus was occupied by the Civil Basilica, while in the northeastern corner of the city walls, a covered theatre was erected.

The western side of the Forum was lined with porticoes and tabernae (shops), while the southern side of the large square was also redesigned: aligned with the Capitolium, a grand building was constructed, possibly identifiable as the Curia, the meeting place of the city council.

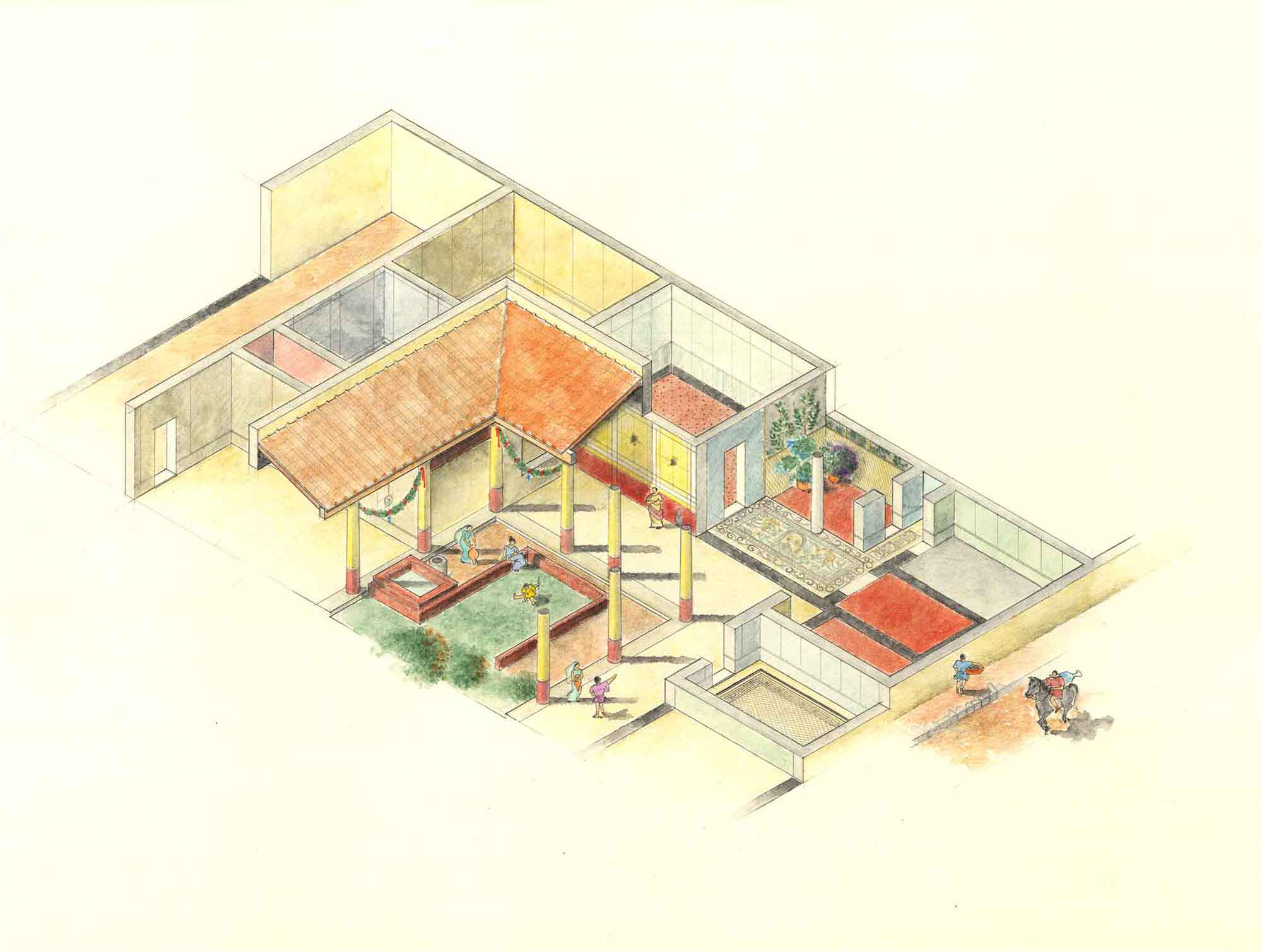

In the early Imperial age, Luna assumed a sumptuous and refined appearance — of which only a few visible traces remain today. Porticoes lined streets paved with large cobblestones; public spaces were covered with precious marble slabs; fountains and gardens adorned both monuments and private homes.

Imposing marble statues of emperors and members of the imperial family filled the arcades and public spaces. This climate of prosperity continued in the following centuries, during the reigns of the Antonine and Severan dynasties (2nd–3rd century CE).

-

Theater

Theater -

Domus of Frescoes

Domus of Frescoes

From the Late 4th Century to Abandonment

In the 4th century, Luna was affected by the widespread crisis that struck the Roman Empire, further worsened by a devastating earthquake — a catastrophic event known only through archaeological evidence, as no written sources mention it.

Modern agricultural practices have partially damaged the settlement rebuilt after the earthquake, destroying the more superficial archaeological layers.

Some areas of the city were restructured through renovation works, in certain cases quite extensive. Examples include interventions in the Domus of the Mosaics, the northern wing of the Forum, and the Civil Basilica — often carried out using reused architectural and decorative materials from buildings destroyed in the disaster.

Significant transformations also occurred in the southwestern sector of the city, where, above the former Domus of Oceanus, a Christian basilica was constructed in the second half of the 5th century. This development reflects the presence of a large Christian community, so prominent that Luni became the seat of a bishopric.

In 552, following its military occupation by General Narses, Luni became the center of the Byzantine province of Maritima Italorum, and its church was completely renovated.

According to historical tradition, in 643 the Lombard king Rothari destroyed Luni’s defensive walls and ravaged the city. However, during Lombard rule, the bishops of Luni retained a significant degree of political and administrative autonomy.

A devotional chronicle recounts that in 782, the wooden crucifix carved by Nicodemus of Arimathea, known as the Holy Face, arrived in Luni, which at the time also housed the ampoule of the Blood of Christ: this relic was placed in Luni’s cathedral, dedicated to Saint Mary, which underwent major renovations during the Carolingian era, including the construction of its first semi-annular crypt and the chamber of the reliquaries.

According to historical tradition, in 643 the Lombard king Rothari destroyed Luni’s defensive walls and ravaged the city. However, during Lombard rule, the bishops of Luni retained a significant degree of political and administrative autonomy.

Tower of the Byzantine defensive wall

In 845, Luni became part of the March of Tuscia, under the control of the Adalberti family. A testimony by Prudentius, Bishop of Troyes, reports that in 849, Mauri et Sarraceni raided the coast from Luni to Provence without encountering resistance.

In 860, one of the most legendary episodes in Luni's history took place in its cathedral: the Danish pirate Hasting, having faked his death, is said to have "risen" from his coffin during his own funeral ceremony, held in the church, and then proceeded to plunder the city—believing it to be Rome.

Following the coronation of Berengar II as King of Italy in 966, Luni, now part of the Obertenghi March, was equipped with a fleet to defend itself against Muslim incursions. Nevertheless, in 1015, pirates from the fleet of Mujāhid al-ʿĀmirī forced the bishop to flee during a raid on the city.

At the end of the 11th century, as recorded in the Pelavicino Codex, Luni was placed under the protection of Frederick Barbarossa and his son Henry VI, while the bishops were granted the right to impose tolls at the port.

Monetary finds confirm ongoing commercial vitality and trade, suggesting a settlement that was still productive. However, the progressive silting up of the portus Lunae and the spread of malaria led to the gradual abandonment of the coastal plain. This culminated in the transfer of the bishopric to Sarzana in 1204.

Nevertheless, the spiritual and symbolic bond with Luni’s cathedral endured: throughout the 13th century, bishops would return to the ancient site to conduct solemn feudal and religious ceremonies.

In 1306, Dante Alighieri, staying in Sarzana on behalf of the Malaspina family, famously cited Luni among the “dead cities” in his Divina Commedia.

Research history

After the city's abandonment, a process of partial destruction began. Luni became a source of building materials and valuable artifacts for private collections — including that of Lorenzo the Magnificent.

From the 16th century onward, the site — by then the property of the nobility of Sarzana and the clergy of Lunigiana — attracted the attention of cartographers, who documented the ruins that were gradually re-emerging. Among the most notable examples is the detailed work by Matteo and Panfilo Vinzoni, commissioned in the 18th century by the Serenissima Republic of Genoa.

Systematic archaeological research did not begin until the 19th century. One of the earliest excavations was carried out in 1837 by Marquis Angelo Remedi in the western portico of what would later be identified as the Capitolium. Excavations continued under the direction of Carlo Promis, funded by King Charles Albert of Savoy, and led to the discovery of marble statues and other artifacts, many of which were transferred to the Royal Museums of Turin.

In 1842, Remedi also excavated part of what would be recognised as the Temple of the goddess Luna, unearthing a remarkable group of terracotta sculptures. His collection was eventually sold to the Archaeological Museum of Florence in 1882.

In the final decades of the century, Marquis Giacomo Gropallo conducted further investigations, particularly in the area of St. Mary’s Cathedral.

In the early 20th century, Carlo Fabbricotti, a marble industrialist, carried out extensive excavations both within the city and outside its walls, including the clearing of the amphitheatre. He assembled an important collection at his Villa del Colombarotto in Carrara, which also incorporated the Gropallo finds. In 1939, his son Carlo Andrea donated this collection to a consortium of municipalities in the province of La Spezia. These artifacts now form the core of the collections at the “Ubaldo Formentini” Municipal Museum, located in San Giorgio Castle in La Spezia.

It was only with the introduction of the Cultural Heritage Protection Law no. 364 of 1909 that indiscriminate artifact removal — which had previously supplied private collections — came to an end. Archaeological research resumed in the years immediately following World War II, leading to discoveries of great importance. The need to display these finds locally led to the establishment, in 1951, of the first Antiquarium of Luni, housed in the Benettini-Gropallo buildings near the western gate of the ancient city.

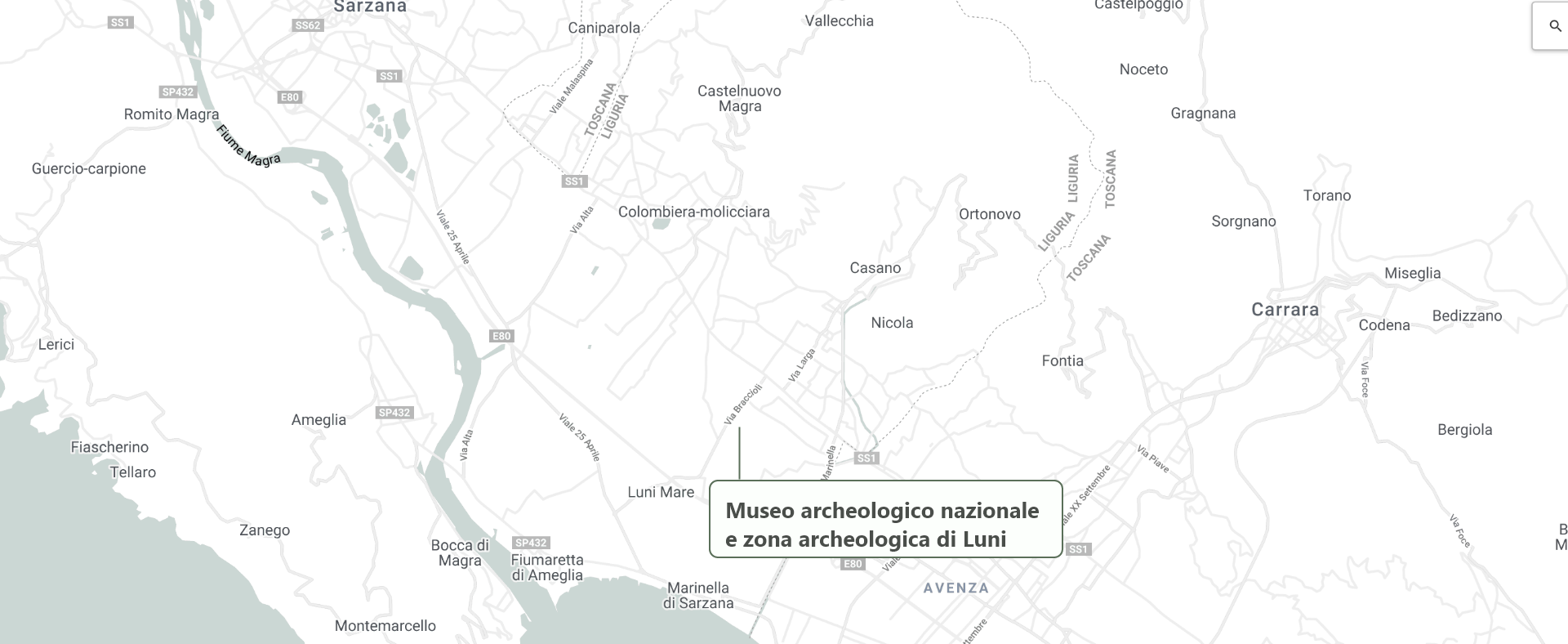

In 1964, the National Archaeological Museum of Luni was officially inaugurated, showcasing materials uncovered both in 19th-century excavations and during more recent campaigns carried out from the 1960s onwards by the Archaeological Superintendency of Liguria.

Since 1967, the state has progressively acquired land and buildings within and around the ancient city, transforming former agricultural plots and rural structures into spaces for public use. This ongoing project led to the establishment of the Museum and Archaeological Area of Luni, with the primary goal of musealising the site and restoring the city’s historical identity.

-

Antiquarium

Antiquarium